Before I drop something at a donation bin or drive-through, I try to picture how I would feel if I saw it on a store shelf. That quick gut check, backed by a few concrete rules, saves me from regret later, whether I am thinking about taxes, privacy, or just not wasting anyone’s time. Here are ten things I now run through every time so my donations actually help and do not quietly end up in the trash.

1. Item Condition

Item condition is the first thing I check, because the IRS only allows deductions for clothing and household goods that are in “good used condition or better.” A tax planning guide explains that The IRS will not let You deduct a worn-out shirt or a broken lamp, and it specifically points to clothing without stains, tears, or obvious damage as the standard. If I would be embarrassed to give it to a friend, I assume it will not qualify.

That rule is not just about paperwork, it shapes what charities can actually sell. When I donate only items in solid shape, I help stores avoid sorting piles of unusable stuff and keep their shelves filled with things people are proud to buy. It also protects me from overestimating my deduction and getting a nasty surprise if my return is ever questioned.

2. Hygiene Standards

Hygiene standards are my next filter, because even a structurally perfect item can be unusable if it is dirty. Goodwill Industries has reported that about 15% of donations are rejected for hygiene reasons, including unwashed linens and heavy pet hair, which means a big chunk of people’s good intentions never reaches the sales floor. When I look at a bag of clothes or bedding, I ask whether it smells fresh and looks like something I would put on my own bed right now.

Taking the time to wash, lint-roll, and neatly fold things is not just about politeness, it directly affects how much money a charity can raise. Clean, presentable items move quickly and bring in more revenue, while grimy ones cost staff time and disposal fees. I also avoid tossing in anything with lingering odors from smoke or strong perfume, because those are almost guaranteed to be pulled and discarded.

3. Personal Data Removal

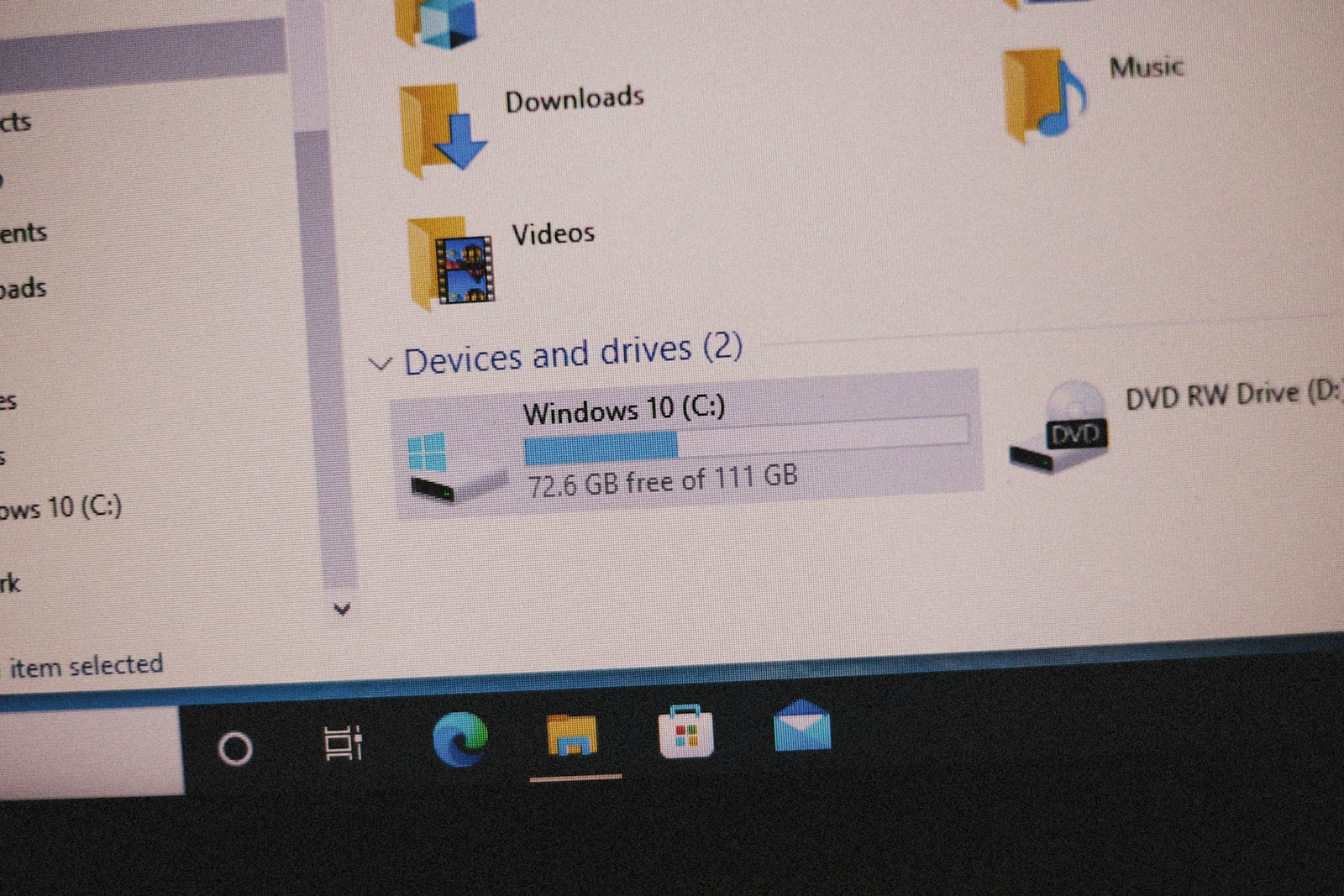

Personal data removal is non‑negotiable whenever I donate electronics. Salvation Army guidelines tell donors to wipe hard drives and remove personal identification from laptops, phones, and tablets, and they point to a Federal Trade Commission report that counted about 1.4 million identity theft cases tied to discarded devices. Before I hand over an old MacBook or Android phone, I factory‑reset it, sign out of cloud accounts, and pull any SIM or memory cards.

I also think about less obvious data trails, like saved Wi‑Fi networks on a router or address books on a smart speaker. If I am not confident I can fully erase something, I look up the manufacturer’s instructions or choose certified recycling instead of donation. That extra step protects me, but it also protects the charity from accidentally passing along a device that could expose someone else’s information later.

4. Value Assessment

Value assessment matters when I am donating anything that might be worth real money, from artwork to a high‑end bicycle. IRS rules in Publication 561 say that if I give an item of used clothing that is in good used condition or better to the Salvation Army, the FMV, or fair market value, is the price typical buyers actually pay. For items valued over $5,000, I need a qualified appraisal, and if my total non‑cash gifts top $500, I have to attach Form 8283.

One guide on Noncash Charitable Contributions spells out that Yes, Form 8283 is required for donations between $500 and $5,000, and Completing Section A is enough at that level. Knowing those thresholds keeps me from guessing at values or skipping documentation that the IRS expects. It also nudges me to keep receipts and photos so I can back up what I claim if anyone ever asks how I arrived at a number.

5. Size Compatibility

Size compatibility is a surprisingly big deal, especially with furniture. The Habitat for Humanity ReStore donor guide warns that oversized or non‑functional pieces, such as couches over 8 feet long, often cannot be accepted because trucks and showrooms have limits, and that reality drives about a 20% rejection rate. When I am eyeing a sectional or a massive entertainment center, I measure it and compare it to those kinds of cutoffs before I schedule a pickup.

Thinking about size also helps me avoid off‑loading something that will just become a burden for volunteers. If a dresser is too heavy for two people to move safely or a table will not fit through a standard doorway, I consider disassembling it or finding another outlet. Matching what I give to what stores can actually handle keeps my donation from stalling in a warehouse or being quietly scrapped.

6. Hazardous Materials

Hazardous materials are another area where I slow down and double‑check. The EPA’s recycling data notes that batteries and many electronics contain substances that fall under RCRA hazardous waste rules, and improper handling can trigger fines of up to $50,000. That means I cannot just toss a box of old lithium‑ion batteries or a leaking UPS backup into a donation pile and hope for the best.

Instead, I look for battery compartments, swollen packs, or labels mentioning lead, mercury, or other regulated materials before I donate. If something looks risky, I route it to a household hazardous waste program or an e‑waste event rather than a thrift store. That choice protects staff and shoppers from exposure and keeps the charity from being stuck with a dangerous item it is not equipped to manage.

7. Expiration Dates

Expiration dates are critical whenever I am donating FOOD, especially to pantries or disaster relief drives. A Red Cross inventory summary shows that expired or near‑expired items are pulled immediately, and about 10% of incoming perishables are discarded for that reason. I now flip every can and box to check the Best or “best by” date, because once it is past, many organizations will not put it on shelves at all.

That habit lines up with broader guidance on Best and expiration DATA, which explains how confusing labels can lead to unnecessary WASTE. I also keep in mind that One campus food program has said it never allows certain items past a best‑by date on shelves, as noted in feedback archives. Donating food well before those dates means families actually get to use it, instead of volunteers having to throw it away.

8. Allergen Checks

Allergen checks are essential when I donate toys, bedding, or clothing that might end up with kids. St. Vincent de Paul best practices urge donors to verify allergen labels on fabrics and toys, and they point to CDC data showing about 5.6 million allergy‑related emergency visits in the United States every year. That number makes me think twice about tossing in a plush toy without a tag or a blanket that smells strongly of pet dander.

Now I look for clear labels about materials like latex, wool, or specific food residues on kitchen items, and I avoid donating anything that has been heavily exposed to smoke or animals. When I am unsure, I either wash it thoroughly or skip donating it altogether. That small bit of caution can spare a family from a scary reaction and helps charities feel confident about what they put on the floor.

9. Size Matching

Size matching sounds simple, but it can make or break whether clothing actually sells. A local thrift store consortium report from NAUMD notes that mismatched sizes, such as non‑standard European labels that do not line up with local charts, lead to about 25% resale failure. When I donate jeans or jackets, I check that the printed size is legible and, if it runs small or large, I sometimes add a sticky note explaining the fit.

That little bit of clarity helps shoppers trust what they are buying and reduces returns or abandoned items in fitting rooms. It also keeps staff from having to guess whether a “40” on a suit is really comparable to a U.S. medium. By aligning what I give with standard sizing, I increase the odds that my old clothes become someone else’s favorites instead of lingering on a rack.

10. Organization Status

Organization status is the final check I make before I load the car. The Better Business Bureau’s charity guidance stresses confirming that a group is a qualified 501(c)(3) and suggests using tools like Guidestar to verify that status. If an organization is not on that list, donations are not tax‑deductible, and there is a risk that my stuff could be supporting unverified or even misleading causes.

To avoid that, I quickly search the group’s name and look for its 501(c)(3) designation and basic financial information. That habit keeps my records clean and gives me more confidence that my items are funding real programs instead of disappearing into a vague “charity” with no accountability. It is a small step, but it ties everything together so I can donate generously without second‑guessing myself later.

Supporting sources: determining value of donated property.

More from Willow and Hearth:

Leave a Reply