The box was the kind of “later” project everyone has: a shallow cardboard container wedged behind a stack of mismatched batteries and instruction manuals for appliances nobody owns anymore. Inside were postcards—hundreds of them—most with faded pictures of downtown streets, lakeside promenades, and long-gone department stores. My first thought was brutally practical: these are clutter. My second thought was more honest: they’re kind of charming, but surely not important.

Then a neighbor mentioned, almost casually, that early postcards aren’t just cute souvenirs—some are tiny historical documents with real value to collectors and local archives. That was enough to stop my donation-box momentum in its tracks. Now the box sits on my table, and every card gets the same treatment: I read it once for the story, then again for the clues.

The moment “old mail” turned into “local history”

Postcards feel informal by design. They’re quick, public little notes—“Wish you were here,” “Tell Aunt May I’m fine,” “The hotel has electric lights!”—the kinds of messages that were never meant to survive a century. And yet, that’s exactly why they’re so useful: they capture ordinary life without trying to impress anyone.

Local historians love them because they freeze-frame what towns looked like when the “main drag” was still a dirt road or when the riverfront was all warehouses. Collectors like them because early printing styles, scarce views, and short-lived publishers can make certain cards genuinely rare. Even a card that’s not worth much money can still be valuable evidence, especially if it shows a building before a remodel, a streetcar line that’s been forgotten, or a storefront name nobody can find in city directories.

Why early prints can be more than pretty pictures

Not all postcards are created equal, and the older ones often carry more weight. In the U.S., many collectors pay special attention to the “Golden Age” of postcards—roughly 1900 to 1920—when postcards were a primary way people shared travel, news, and everyday updates. Those cards can feature early photo processes, vivid color lithography, or “real photo postcards” made from actual photographic paper rather than mass-printed ink.

There’s also a practical reason early prints matter: towns change faster than you think. A postcard might show the only known image of a small train depot, a dance pavilion, a flood before a new levee, or a neighborhood business district before urban renewal. That sort of detail is catnip for anyone trying to reconstruct a community’s past—sometimes more revealing than the official photos that were staged and scrubbed clean.

What I started looking for on the back (and why it matters)

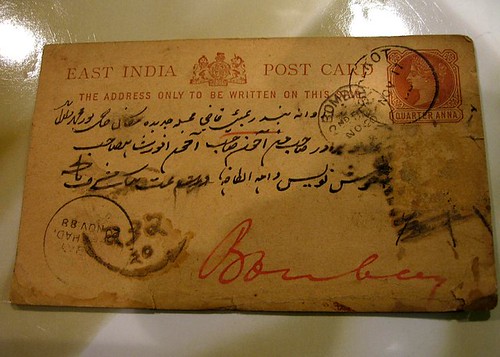

I used to flip postcards over only to see if someone had written anything fun. Now I check the back like I’m decoding a small mystery. Postmarks can pinpoint dates, and even a barely readable stamp cancellation can put a card in the right decade.

Then there are addresses and names. A postcard sent to “Mrs. E. Whitaker, above the millinery” is basically a breadcrumb trail for genealogists, and it can tie a photo to a specific person or business. Messages themselves can be surprisingly specific—mentioning a factory opening, a church social, or a storm that knocked out power—little details that don’t always make it into newspapers.

The front has clues too: printing styles, captions, and tiny errors

The picture side tells its own story, especially if you slow down. Captions like “New High School (Dedicated 1912)” or “Main Street After the Fire” are a gift, but even generic labels can help confirm a location or an old street name. If there’s a photographer’s credit, publisher imprint, or series number, that can matter to collectors who track regional producers.

And yes, the weird stuff can be useful. Misspellings, outdated place names, and “temporary” attractions—like a short-lived amusement park—can make a card more interesting, not less. I’ve learned not to assume a card is common just because the scene looks ordinary; sometimes the most ordinary view is the one nobody bothered to keep.

Condition counts, but it’s not the whole story

If you’ve ever watched someone judge a used book by its spine, you’ll understand postcard condition talk. Creases, heavy corner bumps, stains, and writing that bleeds through can reduce collector value. But for historical interest, condition isn’t always a dealbreaker—especially if the image is rare or the message mentions something specific.

One card in my box has a coffee ring like it survived a train station diner in 1915. It’s not pretty, but the note describes a streetcar strike and names the line. If a local archive didn’t already have that detail tied to a date, that messy little ring might be the least important part of the card.

How people figure out what a postcard might be worth

“Valuable” can mean a few different things here. Some postcards sell for a couple dollars, others for much more—especially real photo postcards, scarce regional views, early holiday cards, or cards tied to notable events. The best way to get a reality check is to look up similar cards on marketplaces and focus on sold prices, not hopeful listings with sky-high numbers.

Local relevance can raise the stakes too. A card of a small-town bridge might be a shrug online, but it can be a treasure in that town, particularly if the bridge is gone. And if a postcard includes a unique view—an interior of a shop, a school classroom, a factory floor—it can attract both collectors and institutions even if the condition is only fair.

What to do before you toss, donate, or sell

First, don’t “clean” them in a panic. Erasing pencil notes, scrubbing marks, or trying to flatten a crease with heat can do more harm than good and can remove exactly the details that make the card interesting. If you’re sorting, handle them with clean, dry hands and keep them away from food and sunlight—speaking from experience, it’s shockingly easy to drop a crumb onto 1908.

If you want to keep them, archival sleeves or acid-free boxes help, but even a simple, dry, stable storage spot is an improvement over a damp basement. If you want to sell, grouping by theme or location usually works better than a single giant lot, because collectors search for specific towns, railways, hotels, or events. And if you suspect a batch is locally significant, consider contacting a local historical society or library; many welcome scans or donations, especially if the images fill gaps in their collections.

The drawer doesn’t feel like clutter anymore

The funny thing is, the postcards didn’t change—my idea of what they were changed. What looked like disposable travel ephemera started reading like a community’s casual diary, one hurried note at a time. Some are silly, some are sweet, and a few are unexpectedly moving in the way only ordinary words can be.

I still might not keep every single one. But now, before anything leaves the house, I check the date, the place name, the publisher, and the message—then I check again, just to be sure. It turns out the difference between “junk drawer” and “local history” can be as thin as cardstock.

More from Willow and Hearth:

Leave a Reply